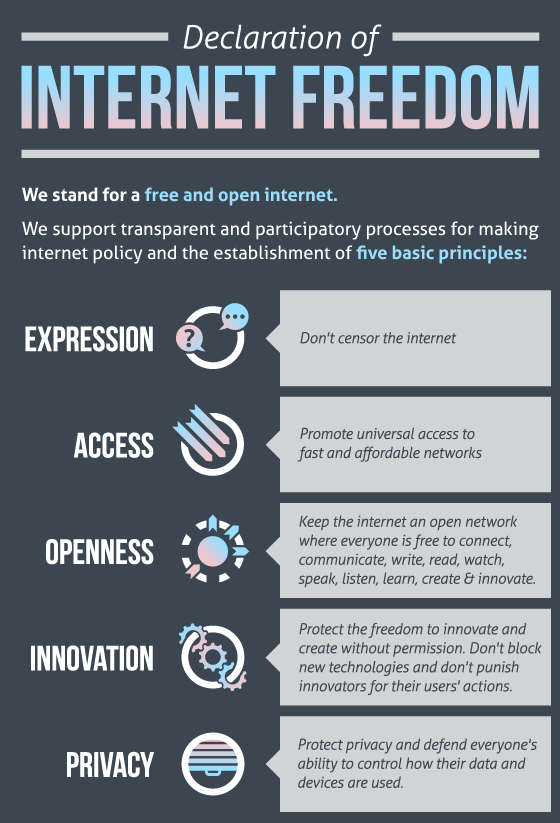

The Declaration of Internet Freedom

This post originally appeared in Slate.

Internet freedom isn’t a left or right issue — it should matter to everyone who cares about the health and future of democracy.

Today a full third of the world’s population is now online. And as the importance of the Internet as a platform for participation and expression increases, it’s all the more vital that we keep it open and free from censorship, surveillance and discrimination.

At this very moment, opposing political, commercial and ideological forces are fighting to determine how open or closed the Internet will become. Fundamentally, we are faced with the very real possibility that the most important communications platform in society today could devolve into a fragmented, censored archipelago.

But there are signs that we can avoid that fate. On Jan. 18, more than 100,000 websites and more than 7 million users spoke out against the Stop Online Piracy Act and the Protect IP Act, two bills in Congress that would have undermined participatory democracy and human rights by censoring the Internet. As much as this battle demonstrated the power of online organizing, it also demonstrated the need for a proactive vision for the future of the Internet.

Today, we — representatives of the New America Foundation’s Open Technology Institute and Free Press — join more than 100 organizations, ranging from Amnesty International and the Electronic Frontier Foundation to Mozilla and Cheezburger, Inc., in announcing a Declaration of Internet Freedom. Centered on core principles of free expression, access, openness, innovation and privacy, the declaration's goal is to spark a global discussion among Internet users and communities about the Internet and our role in protecting it.

The Internet is now inseparable from the functioning of democracy. When corporations or governments undermine freedom of expression online or block innovative technologies, they manipulate the democratic process, marginalize important constituencies and often silence voices of dissent.

In December 2011, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton warned: “Fragmenting the global Internet by erecting barriers around national Internets would change the landscape of cyberspace.” And the call for Internet freedom has united strange political bedfellows like Sen. Ron Wyden, D-Ore., and Rep. Darrell Issa, R-Calif. International leaders are engaged in this discussion as well. Swedish Foreign Minister Carl Bildt declared that “cyber walls are as certain to fall as the walls of concrete once did.”

Internet freedom as a foreign policy complements but does not replace the imperative of extending democratic process and human rights provisions to the Internet. Egyptian blogger and activist Alaa Abd El-Fattah has urged those in the West to “fight the troubling trends emerging in your own backyards,” citing battles such as Network Neutrality and “draconian copyright.”

As a global interconnected platform, the Internet has tremendous potential for cross-cultural conversations and debate, but only insofar as the medium remains free from government and commercial censorship and abuse.

The Declaration of Internet Freedom is offered as a starting point to reinforce this conversation and to demonstrate that the remarkable coalition that came together around the SOPA fight was not ephemeral.

As representatives of groups based in the United States, we have an eye on domestic policy — and a belief that Internet freedom starts at home — but we believe these principles have global appeal and importance.

It’s essential to emphasize that the declaration is designed not to be the final word but rather to spark a much larger discussion. If you agree with the principles we’ve crafted, we welcome you to sign on. But we are just as interested in why you disagree with them or what you think is missing.

And we hope you will debate them, translate them, make them your own, and broaden the discussion with your community, as only the Internet makes possible.

Sascha Meinrath is the director of the New America Foundation’s Open Technology Institute. Craig Aaron is the president and CEO of Free Press.