To Plead Our Own Cause

This post originally appeared on BKNation.org.

“We wish to plead our own cause. Too long have others spoken for us.”

—Freedom’s Journal, the first African-American newspaper (1827)

What if you had to pick five websites to browse for the rest of your life? What websites would make your list?

I’d imagine one would have to be BK Nation (shameless plug), another your preferred email website (Gmail, Yahoo, Hotmail). Where would you go for news — Democracy Now, Colorlines … or would you pick a news giant like CNN, MSNBC or (gulp) Fox News? For sports would you follow Dave Zirin’s Edge of Sports or settle for Disney-owned ESPN? How about social media; does Facebook make the cut over Twitter, or perhaps Instagram emerges as your pic (pun intended)?

Let’s try another example. What if your community was being discriminated against, and you wanted to tell the world what was happening. You wanted to organize so that together you could build collective power, be heard and “rise above the narrow confines of individualistic concerns to the broader concerns” of your community’s well-being.

What if a multinational corporation decided that didn’t fit into its best interests. So it made sure you had no platforms or tools to ensure your community’s voice is heard. What if you were powerless to organize for a better future?

It seems strange to think any of this could be a possibility in the 21st century and post-King world. Yes, it’s purely hypothetical, but the reality is not far behind.

Recently, a federal court struck down Net Neutrality — a set of open Internet rules passed by the Federal Communications Commission that prohibited Internet service providers from blocking and discriminating against websites.

The consequences of this court decision are not just about what websites we’ll have access to consume, but about who has a right to be heard. For marginalized communities the Internet represents a place for our stories to be told without the usual filters of mainstream media that portray our communities as a series of stereotypes and problems.

Platforms of dissent have a historical legacy in fighting racism, from the role of black-owned newspapers in the abolitionist struggle to the way Dr. Martin Luther King used radio and TV to shine a light on the cause for racial equality. As my comrade Malkia Cyril, executive director of the Center for Media Justice, points out, ending Net Neutrality carries real material consequences for communities of color:

For those of us already pushed to the margins of public debate, the court’s decision to strike down Net Neutrality couldn’t be worse. Despite reports by telecom companies and their allies that keeping the Internet open would hinder jobs and hurt the economy, the opposite is true. In a David vs. Goliath battle for visibility, eliminating the only rules that allow David’s voice to be heard on the Internet is an economic death sentence communities of color can’t afford.

In the aftermath of this decision is an Internet in which corporations like Verizon, AT&T, Comcast and Time Warner can editorialize the Web to maximize their profits. Verizon has already demonstrated a tendency to censor speech if it reflects views it disagrees with. Other companies have already created pay-to-play schemes dictating what their customers can access, and without Net Neutrality, we’re likely to see more examples in the near future.

But as Dr. King said, “Only when it is dark enough can you see the stars.” The court’s decision was based on a legal technicality, brought on by the way the FCC has chosen to regulate the Internet. It’s a technicality the Federal Communications Commission can easily overcome if it chooses to treat the Internet like a utility everyone deserves access to, versus a luxury only those who can afford it enjoy.

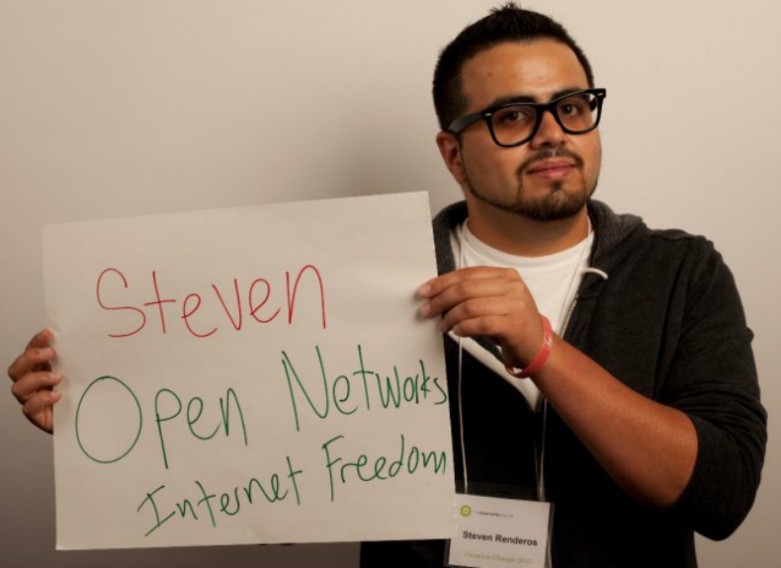

Companies like Verizon and AT&T are already lining up outside the doors of the FCC to make sure that doesn’t happen. But we’re lining up to be heard too. Networks like Voices for Internet Freedom are calling on the FCC to regulate the Internet as the essential telecommunications service that it is.

Thanks to the grassroots leaders of yesterday, today and tomorrow, we know we’re not voiceless; it is simply a matter of making sure we’re being heard. By working together, we can ensure that our signal to the FCC, government bodies and billion-dollar corporations like Verizon comes in loud and clear.