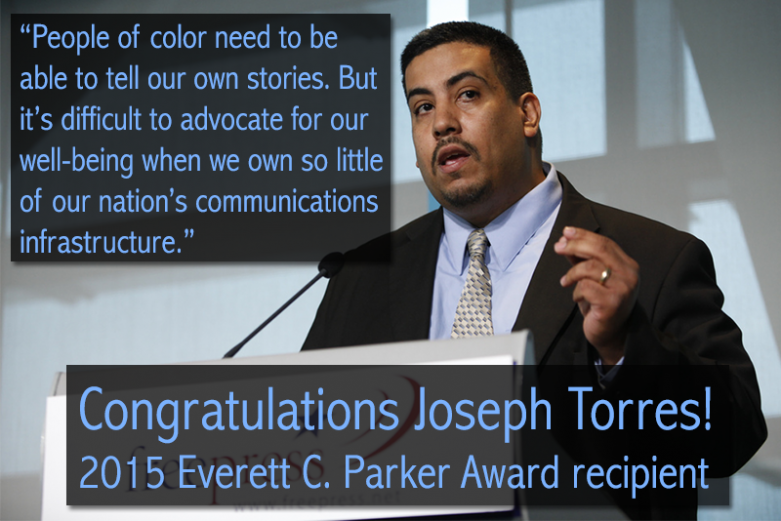

Free Press' Joseph Torres Hailed for His Role in the Fight for Racial Justice

On Oct. 20, 2015, Free Press’ amazing senior external affairs director, Joseph Torres, received the Everett C. Parker Award, given in recognition of an individual whose work embodies the principles and values of the public interest in telecommunications and the media. Dr. Parker founded the media justice ministry of the United Church of Christ (UCC), and recently passed away at the age of 102.

The text of Joseph’s inspiring acceptance speech follows below.

I want to say how incredibly honored I am to receive this award named after Dr. Parker.

I had the honor of meeting Dr. Parker on a couple of occasions, and I feel so grateful to be a part of the struggle that he and so many others spent their lives fighting.

People of color have always struggled and fought to make sure their voices are heard in the media. It’s why we created our own newspapers 200 years ago and why we go online today.

But it has never been in the interest of those in power to allow our voices to speak or be heard.

It wasn’t in Jackson, Mississippi, during the 1960s when Dr. Parker and Black local civil rights leaders challenged the TV license of WLBT, a racist station that used the public airwaves to prevent integration and preserve a separate and unequal society.

At the time, U.S. residents didn’t have the legal right to challenge a broadcast license, even one run by a white supremacist. But the UCC lawsuit changed history when a federal court ruled that everyday people could challenge FCC policy.

This unleashed a new era of media activism. Black and Brown civil rights leaders demanded that broadcasters hire people of color and air programming that informed rather than demonize their communities.

From 1971–1973, more than 340 license challenges were filed, mainly by civil rights groups. This uprising forced the industry to hire the first wave of journalists of color to integrate its newsrooms.

But 40 years later, it’s easy to be discouraged by the lack of progress. There are too few journalists of color working in newsrooms today and still too much media coverage that marginalizes our community.

Because throughout history, people of color have been covered as a threat to society.

Back in the early 1700s, the colonial Boston News Letter wrote that Blacks were addicted to stealing and lying.

In 2011, a Pew report on the Pittsburgh media market found that “Of the nearly 5,000 stories studied in both print and broadcast, less than 4 percent featured an African American male engaged in a subject other than crime or sports.”

As the journalist Stacey Patton recently said, “The American mainstream media is working exactly the way it should. A racist society requires media bias. A racist society requires coverage of people of color that aligns and overlaps with broader racist sentiments and stereotypes.”

The struggle for racial justice is very much dependent on access to the media so we can tell our own stories. But this is hard to do when you’re dependent on corporate gatekeepers to tell your story, when people of color own few broadcast stations and cable outlets, when our nation’s media policies are shaped by structural racism.

This is why the fight over the future of the open Internet, over Net Neutrality, is so central to this struggle for racial justice. It’s provided the digital oxygen that has helped breathe life into the movement that cries out Black Lives Matter, Not One More and Say Her Name.

But while the Internet can be a tool for liberation, we know it can also be used as a tool for our oppression through mass government and corporate surveillance.

But we’re able to fight back today because Dr. Parker and Black leaders fought in Jackson to ensure our voices weren’t silenced.

We’re able to fight because Al Kramer of the Citizens Communications Center worked with the community to force broadcasters to hire people of color.

We’re able to fight because William Wright of Black Efforts for Soul in Television organized the Black community to stand up to institutional racism in the media.

We’re able to fight because Emma Bowen was troubled by the impact of the media on the Black community and founded Black Citizens for a Fair Media.

We’re able to fight because journalists like Juan González and Charlie Ericksen (two close friends and mentors of mine) have exposed the media bias that is harming the Latino community.

And we’re able to fight today because a new generation of activists is demanding a just media system that ensures broadband is an affordable lifeline, that fights predatory prison-phone rates, that fights the targeted surveillance of communities of color, that fights for an open Internet that allows our voices to be heard and never silenced, and that fights for journalism that seeks to expose institutional racism rather than protect it.

This is why I’m honored to receive this award. It validates that we are on the right path that so many have fought so hard for us to walk on.

I want to thank my Free Press family for giving me the opportunity to be a part of this noble struggle, especially Craig Aaron, Kimberly Longey, Matt Wood and Misty Perez Truedson.

I also want to thank my media justice and civil rights family: Malkia Cyril, Steven Renderos, Brandi Collins, Rashad Robinson, James Rucker, Jessica Gonzalez, Michael Scurato, Alex Nogales and so many others for allowing to me to lock arms with them in service to this struggle, because in order to achieve racial justice, we must have a just media system.

I also want to thank my family, my wife, for all of their support. I especially want to thank my wonderful daughter Charis who is with me today.

I am also so proud to stand alongside Wally Bowen, who has fought to ensure people have access to modern telecommunications regardless of where they live or how much they make.

Finally, I want to thank Chance Williams for flying to be here today and Cheryl Leanza, the United Church of Christ and the selection committee for believing I am worthy of this recognition.

Rest in power, Everett Parker.