Dear Chairman Wheeler: The State of Broadband Is Hurting Vulnerable Communities

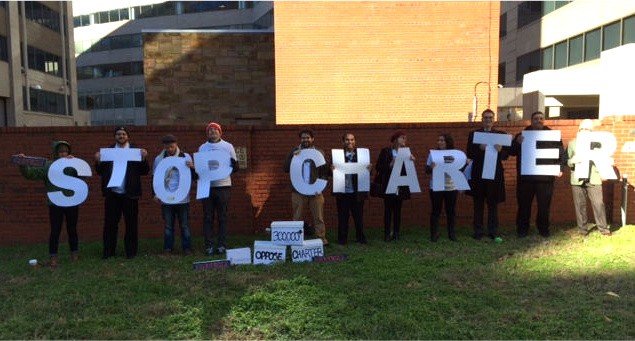

Tom Wheeler, the chairman of the Federal Communications Commission, will soon decide whether to approve or deny Charter’s proposed $90 billion acquisition of Time Warner Cable and Bright House Networks.

We believe the decision is an easy one.

If the chairman is concerned with the state of the cable and broadband industry, then the choice is simple: Block the merger.

But if the current reality for broadband and cable customers isn’t enough to motivate Wheeler, we urge the chairman to listen to the canary in the coal mine to hear a larger truth.

The broadband marketplace isn’t just broken; it’s harming millions of our society’s most vulnerable members, who are unable to afford at-home broadband service. This comes at a time when having Internet access is essential to filling out a job application, completing homework or applying for government services.

A recent Pew Research Center report found that U.S. broadband-adoption rates among adults dropped from 70 percent in 2013 to 67 percent in 2015. The numbers are even more dismal among communities of color: Adoption plummeted from 62 percent to 54 percent for Black households and from 56 percent to 50 percent for Latino homes.

Pew found that price was a primary reason for this decline. Broadband is too expensive yet it’s undeniable that people need it.

And a lack of options is the main reason it’s too costly for so many households to subscribe to broadband. According to Wheeler, “three-quarters of American homes have no competitive choice” for truly high-speed broadband access.

Over the years, the FCC has allowed the industry to consolidate. That’s driven up prices and made it harder for poorer households to adopt broadband. In the absence of choices for users, providers can charge whatever rates they want.

This is why the FCC should reject the Charter merger. If approved, Charter would become the nation’s second-biggest cable company, just behind Comcast. Together the two companies would control nearly two-thirds of existing broadband customers, creating a duopoly. And the newly merged Charter would face competition from providers that can truly match its broadband speeds in only 10 percent of its territory.

In addition, Charter would have a whopping $66 billion in debt (combining its current debt and new debt just for this deal). The new company would have the ability and the incentive — $66 billion worth of incentives — to raise the price for broadband in all of the areas Charter and Time Warner Cable cover today, which include our nation’s two largest cities: New York City and Los Angeles. This would make it harder for many struggling Black and Latino households and low-income families to afford or adopt broadband. Charter would also be the main cable broadband provider in large cities like Dallas, Cleveland and Charlotte, to name just a few.

The digital divide in cities like these has contributed to the growing inequity within society.

Pew found that a greater percentage of Black, Latino and young adults said that being unable to afford home broadband places them at a major disadvantage in finding out about job opportunities, accessing government services, getting health information or learning about things to enrich their lives.

In addition, broadening the digital divide would make it harder for students of color, who make up more than half of all elementary school-aged children, to overcome the challenges they already face to achieve academically.

This social inequality would be passed on to future generations.

By approving massive mergers, the FCC has played a central role in creating inequity in the broadband market. To justify its decisions the agency has often cited the merging companies’ pledges to create a low-cost, home-Internet service.

That was a major reason the Commission approved the AT&T-Bell South merger in 2006 and the Comcast-NBCUniversal merger in 2011. Now Charter’s using the same tactic.

These programs make for great PR but fail to make a dent in the digital divide. While a program like Comcast’s Internet Essentials provides a low-cost option to some people, its criteria has made it difficult for eligible families to sign up, and it initially excluded seniors and families without children. Having a limited low-cost option available to just the poorest among us doesn’t lower broadband prices overall, while a lack of choices has ensured that these prices stay high.

That means these Internet service providers are responsible for creating the digital divide. Instead of expanding capacity and making broadband affordable, these companies would rather limit output and keep their prices high to maximize profits for their shareholders.

This is how monopolists act.

But it doesn’t have to be this way.

During his tenure, Chairman Wheeler has expressed concerns over the lack of competition in the broadband industry.

In 2014, he said that “meaningful competition for high-speed wired broadband is lacking and Americans need more competitive choices for faster and better Internet connections.”

And in a recent speech in Philadelphia, the chairman admitted he “has not done enough” to promote competition.

Chairman Wheeler showed political courage when he blocked the Comcast-Time Warner Cable merger, which would have crushed competition.

This is why it’s critical for him to muster up the same political courage to block the Charter merger.

We urge Wheeler to turn his words into action and to listen to the canaries in the coal mines in cities across the country — the millions of households that have never adopted home broadband, or had to give it up because they could no longer afford it.

The decline in broadband adoption should serve as a major warning sign that the structural integrity of the broadband market is compromised — and that structural change is needed. That starts with blocking bad mergers rather than ignoring the harms they cause.